On a strange and distressing day, an old method for moving forward.

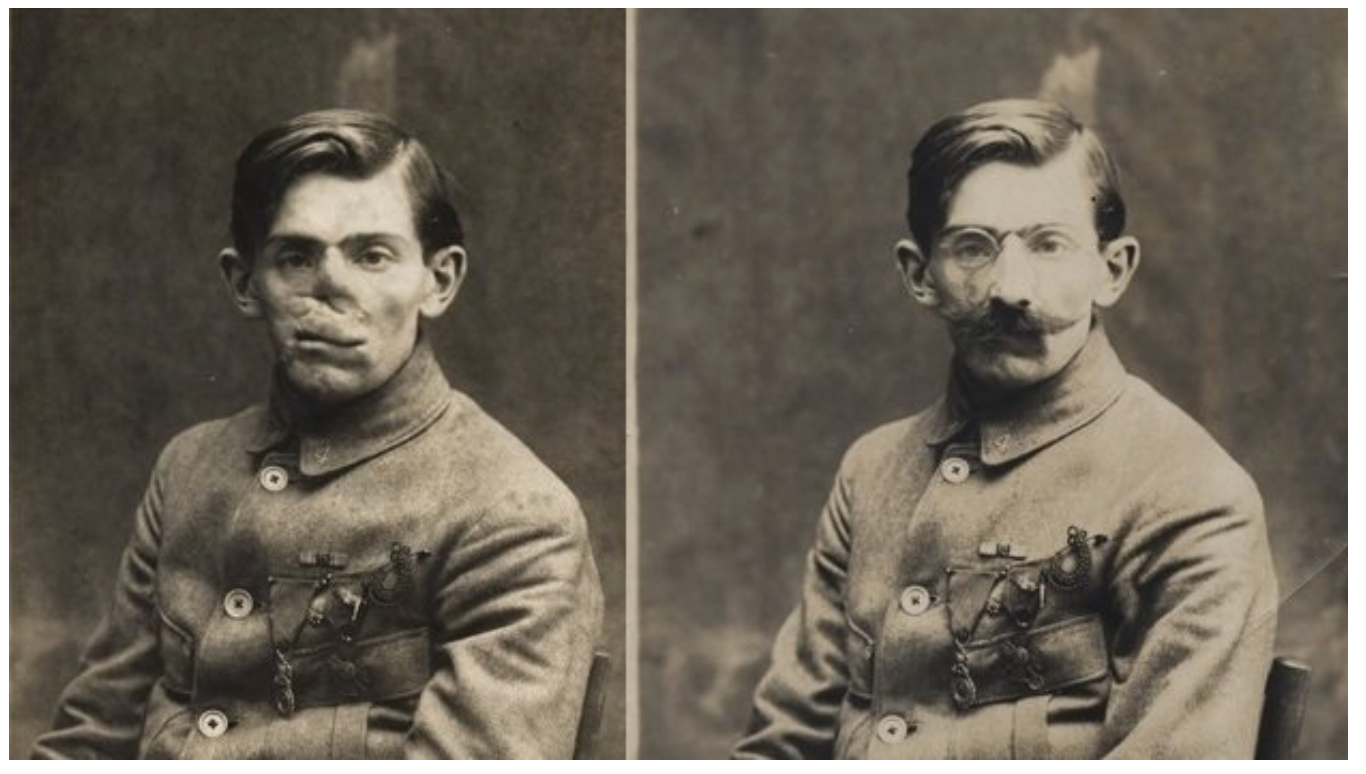

Work by Anna Coleman Ladd, via NPR.

Work by Anna Coleman Ladd, via NPR.

Injuries aquired during WWI trench warfare frequently came from a basic miscalculation: how quickly someone could peer up and over the abyss vs. how quickly the bullets from a machine gun flew.

As one wounded soldier put it, "It sounded to me like some one had dropped a glass bottle into a porcelain bathtub."

So what then? Plaster, tin, and clay.

Masks did not hide the fact of damage, but they obscured the extent. They prevented the involuntary moment of shock and revulsion.

It was an imperfect solution for many reasons. Just one expression was possible, for starters, and sculptors, no matter how talented, were subject to the light. Balancing skin colors was a fine art, but no one could impose chamillion-like abilities onto artificial skin. Perhaps their greatest success is precisely how we see them now: in photographs, without movement. But no one, even today, can completely undo what a bullet to the face does, though the patient may well be lucky enough to continue limping along in this world.

There is probably a metaphor here. But for me it's enough, at least for today, to allow objects to be literal.