The Brown Dog, Part II: Swedish Women in the English Medical Establishment

Saturday, November 19, 2016 at 4:46PM

Saturday, November 19, 2016 at 4:46PM I stumbled on this story online once, years ago, somewhere in the vicinity of eleven o'clock at night.

It goes like this:

In 1902, two Swedish women, well born, financially independent, and eager to create substantive change, enroll in The London School of Medicine for Women. Their names were Lizzy Lind af-Hageby and Leisa Katherine Schartau. Their motive? Reveal to the public the true horrors of vivisection. Their school was anti-vivisection (hospitals and schools generally picked sides), but their status as students allowed them to attend lectures at various other medical training institutions that were not.

They attended hundreds of lectures and over 40 vivisections, keeping detailed notes. Finally, they witnessed the incident of the brown dog.

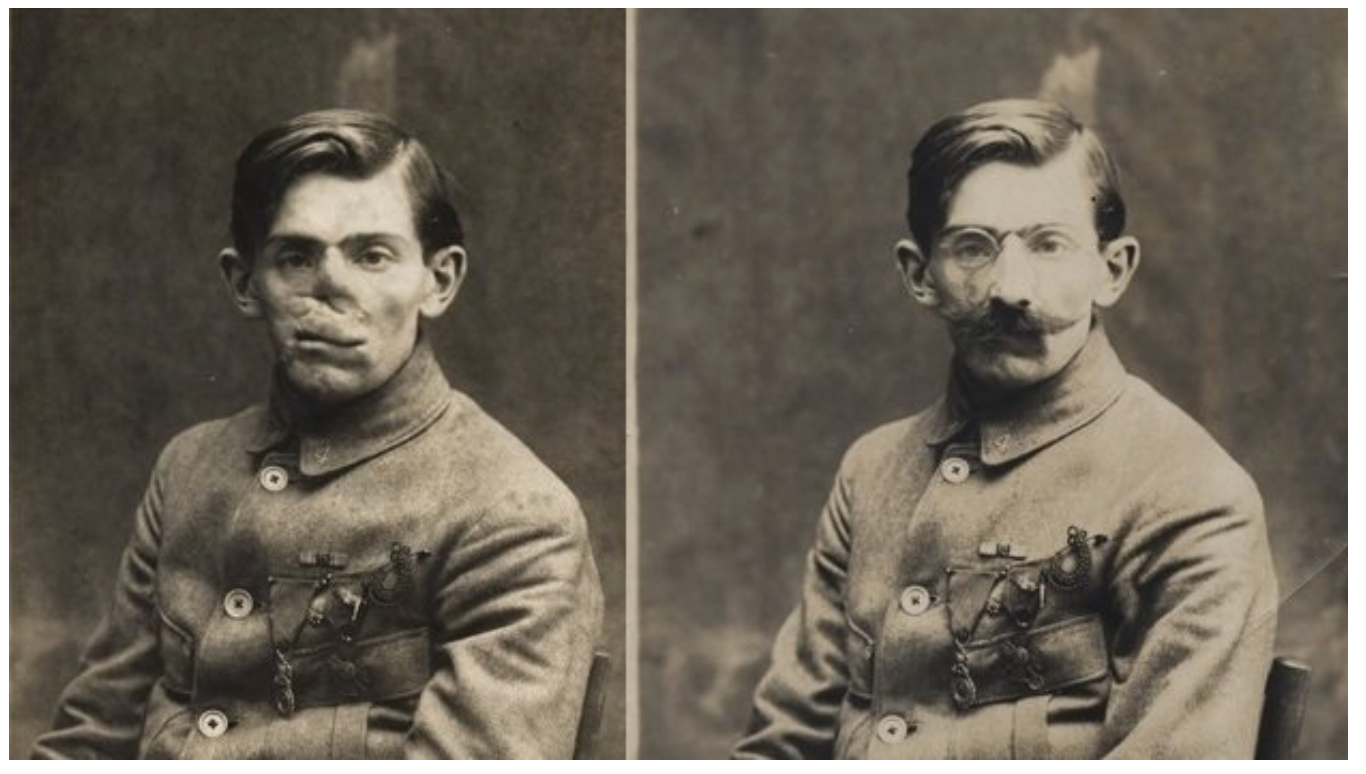

The brown dog himself was non-descript; a mediumish terrier. Brown. However, it was clear to both women when he made his doggy appearance in the lecture hall, muzzled and strapped down on a board, that he had been the subject of a previous surgery. The fact that the first thing the lecturers did was cut him open to check on the status of a previous procedure gave it away.

This was key: the 1876 Cruelty to Animals Act made it clear that, excepting only very specific circumstances, animal subjects could be operated upon only once.

The dog did not fulfill the purpose his vivisectioners had in mind for him that day; the demonstration was a failure, and so they had to settle for removing his pancreas.

Later on, there would be disputes about all sorts of things. Was the dog conscious? Moving around and pushing at the restraints? The Swedish women said so; other medical students said not. Was the dog killed via chloroform, as one doctor initially claimed, or was he killed with a knife by the student who removed his pancreas? (The latter, it would turn out.)

The most fundamental question: was the entire setup--the entire operation, if you will--worthwhile?

Assessing worth is not something that should be done lightly, and yet people do it all the time. They do it so lightly they often don't even realize it's being done. This is far easier to pull off as the type of person whose worth is rarely, if ever, assessed.

And then calculate for hindsight. It's simple now to argue that what was done to a nondescript terrier at a time of incredible medical advances was indisputably worthwhile, even if only as a small event in the larger trajectory of history. The grandmothers saved today based on what they learned then--even the nondescript twenty-first century terriers saved, based on what they learned then--aren't these lives fair to add to the sum on the side of worth?

But trajectories are retrospective, no matter how the physics texts would have it. In hindsight, fate either intervened, or it did not. The stars aligned, or they scattered. And in this case, what was done to Dogs in General at That Time led us inexoriably to the medical advances we have now. Or so we tell ourselves. But constellations are chicken scratch patterns scraped-together out of a haphazard night sky; meaning and chaos are far, far closer than we'd like to confess. Who is to say what discoveries might have resulted from a different verdict on the value of a dog? Who can know whether their breakthroughs, in that world, would really have fallen short of our own? We can suspect all we want, but knowing--there's the rub.

All this to say that in 1903, this dog became a big deal.

There were angry speeches both for and against vivisection, there was a trial for libel, there was a ruling in favor of the physicians, there were reams of writing on the subject in the press, both nationally and internationally, Mark Twain's anti-vivisection short story may or may not have been directly influenced by events, and, finally, a memorial statue to the Brown Dog was erected in Battersea.

That last part, according to many of London's medical students, would not stand. The statue was torn down; demonstrations turned to riots, and sides were chosen:

The Swedish Women, Suffragettes, and Trade Unionists vs. Medical Students and Scientists in General.

Now, of course, it's easy to reframe this particular matchup in several ways, depending on the lens you choose to use. Women vs. Men. Anti-establishment vs. Establishment. The Past vs. The Future. The Future vs. The Past. The Moderately Powerful vs. The Extremely Powerful.

What I think it comes down to, myself, is this: The Expendable vs. The Inviolate.

Because few people (few dogs, for that matter) would volunteer for the role of Experimental Surgical Material, certainly fewer then than would now, in the age of reliable anesthetics and halfway-decent outcomes.

So they had to be recruited, and the recruitment had to be justified. And when recruitment didn't work, they had to be compelled. The body was inviolate--that is, the body of a citizen, with full rights, was inviolate. And fortunately, citizens were in short supply.

But women? Laborers? Especially those who today call themselves people of color? There were plenty of those.

And so the physical act of cutting open this dog, severing muscles, veins, and bone, only really made sense in a narrative from the perspective of the inviolate. There was meaning from this vantage point. There was sacrifice, certainly, but not the terrifying type, the type that might call for backup. There was a world, and it was orderly, and the trajectory bent towards good.

Erecting a statue, however, in memory of what should be nothing more than one data point in that trajectory, turning that data point into a fleshy, breathing creature with enough inherent value to be memorialized? That didn't just threaten the narrative; it completely undermined it. It required an entirely new calculus, one that might result in entirely different conclusions about what was moral and what was not.

Naturally, the narrators didn't like that much. And so the statue came down.

To be continued.