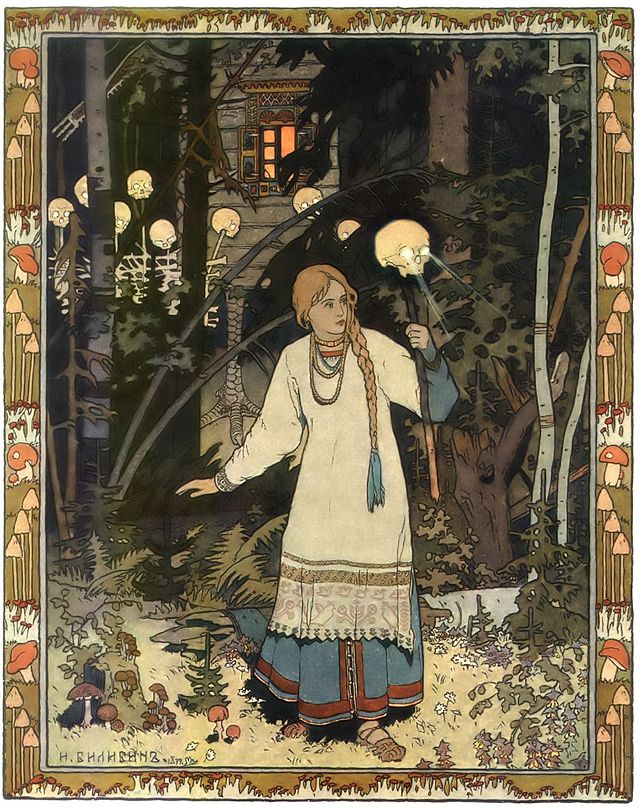

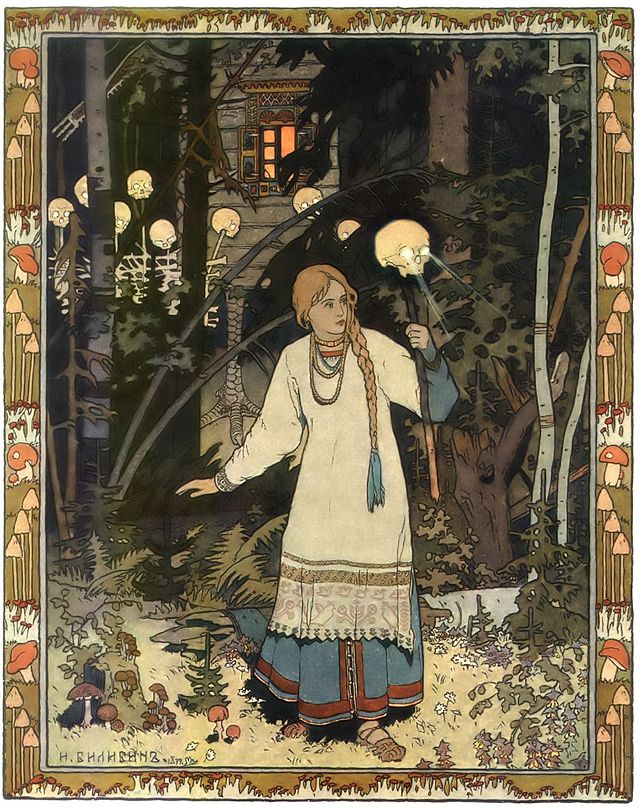

"Vasalisa the Beautiful at the Hut of Baba Yaga" by Ivan Bilibin. Image in the public domain.So the last post, an excerpt from the W.R.S. Ralston collection of Russian Fairy Tales, is the first in a series. I'm in the process of researching Russisan fairy tales for a new project, and there are things in there that are worth sharing. I mean, how do you get any better (or darker, which, honestly, is better) than fiends eating corpses, kids being washed to death in boiling water, huts on chicken legs, skulls for lanterns, and lightly-made, heavily-kept promises?

"Vasalisa the Beautiful at the Hut of Baba Yaga" by Ivan Bilibin. Image in the public domain.So the last post, an excerpt from the W.R.S. Ralston collection of Russian Fairy Tales, is the first in a series. I'm in the process of researching Russisan fairy tales for a new project, and there are things in there that are worth sharing. I mean, how do you get any better (or darker, which, honestly, is better) than fiends eating corpses, kids being washed to death in boiling water, huts on chicken legs, skulls for lanterns, and lightly-made, heavily-kept promises?

I love fairytales and folktales of all kinds, but I've been in love with the concept of Russian fairy tales in particular for years, ever since I was sixteen, sitting in the large main room at the summer camp where I worked one night, listening to a visitor read to us all, about sixty 8-12 year olds and 12 teenaged staffers, from a collection. It was a dark summer night in Sonoma County, too far south for the persistent twilight glow on the horizon that would accompany the telling of these tales in their natural environment. The translation was choppy, as they all are, and the reader was doing just that, reading, and not reciting, not improvising. But it didn't matter--it was the closest I'd been to hearing these stories the way they were probably first told, at just the right time to imagine myself as the kitchen maid who occasionally surfaced (I was, after all, basically a dishwasher), and the atmosphere of that evening has clung to them for me ever since.

Now, I find that I need to know more about these stories. And despite some coursework on fairy tales in grad school, despite teaching a unit on fairy tales each time I taught Children's Literature, I'm not actually familiar with any more than that atmosphere and the basics, Baba Yaga and the Water of Life. So I'll be tracking my exploration of them here. I expect to find the sorts of things that I love finding in other folktales--strange, unquestioned magic, nearly-impossible tasks, unexpected helpers, wise crones, foolish princes, and princely fools--but with a particular flavor to them. For now, I'm continuing with the W.R.S. Ralston version, though I'm listening to it, not reading it, courtesy of Librivox. Starting with Ralston has the added benefit of giving me the 19th century English take on these tales, a perspective not unuseful to this particular project. I'll be keeping you posted.

Tuesday, October 20, 2015 at 3:49PM

Tuesday, October 20, 2015 at 3:49PM  #nanowrimo

#nanowrimo